Wie is verantwoordelijk voor verandering - Een nieuw besturingsmodel

Why this topic still bothers me

For more than three decades, I have been involved in organizational change, sometimes leading it, sometimes advising it, sometimes cleaning up after it. I have worked with executives who genuinely cared, project teams that delivered exactly what was asked, and line managers who did everything they could to keep operations running while “absorbing” yet another change.

And still, I have seen the same pattern repeat itself.

When change struggles, the explanation is often simple: “The line didn’t pick it up.”

Or: “The project delivered, but the organization wasn’t ready.”

Occasionally: “People resisted.”

What rarely gets questioned is the underlying assumption behind all of this: that change management is something a line manager or a project manager can, or should, just do on top of their real job.

I have believed that myself at different moments in my career. Especially when results mattered, timelines were tight, and adding “another role” felt like unnecessary overhead. But experience has a way of teaching you where your own shortcuts stop working.

Over the years, I started to notice something uncomfortable. In organizations where change did stick, where new ways of working survived the first crisis, the first peak, the first leadership change, there was almost always an invisible system at work. Not a glossy change plan. Not a flood of communication. But a deliberate way of thinking about ownership, leadership behavior, reinforcement, and the role of managers in making sense of what was happening.

In organizations where change failed, we often did the opposite. We pushed responsibility downward, assumed capability would somehow appear, and called it “ownership.” When it didn’t work, we blamed execution.

This blog is my attempt to slow that reflex down.

Not to argue that line managers or project managers are doing a poor job, quite the opposite. But to question whether we are asking them to succeed in a system that was never designed for change to succeed in the first place.

Over the years, I’ve learned that change doesn’t fail because people don’t care. It fails because adoption is assumed instead of engineered.

And that is what this blog is really about.

I have read many books and article on this subject over the years, and combined with my experiences, I thought it was about time to combine the two. This blog is my view on change management as I have learned it, and the operating model I now advise organizations to implement and execute.

But first things first, lets start with the usual assumptions in the field.

Change management is often treated like “something the line manager or project manager can just do.”

In many organizations, change management is perceived as soft overhead. Something you can “embed” into the line, or “add” to the project manager’s job. The logic sounds reasonable:

- the line owns performance, so the line should own change

- the project builds the solution, so the project should “manage adoption” too

- dedicated change roles feel like extra cost, and we’re already busy

And yet, the same organizations will say (a few months later):

“We delivered the project… but it didn’t land.”

That gap, delivered but not adopted, is exactly where the research becomes very practical. Because a large chunk of organizational change failure is not about designing the solution; it’s about creating the conditions for consistent, committed use.

1) The category error: adoption is not delivery

A foundational distinction in the literature is that implementation success depends on people actually using the new way of working “appropriately and consistently”, not merely that the solution exists.

Klein & Sorra defined implementation as gaining targeted members’ appropriate, committed use of an innovation, and showed that two things matter disproportionately:

- Implementation climate – do people experience that use is expected, supported, and rewarded?

- Values-fit – does the change align with what people believe matters? 1

This is where many organizations go wrong: they treat change as a project artifact problem (plans, comms, training) when it is often a work environment problem (signals, incentives, management attention, reinforcement, local translation).

Project management delivers the “thing.” Change management builds the conditions for “use.”

Prosci’s benchmarking results2, while practitioner-based, consistently echo this:

success correlates with:

(a) active sponsorship,

(b) dedicated change capacity, and

(c) tight integration with project delivery.

2) Why the “line manager will do it” assumption is half true, and still dangerous

Yes, the line manager is central. People experience change through their direct manager. But the research on middle managers is very clear: they are not just “communication channels.” They are change intermediaries who translate strategy into local meaning and action.

- Balogun’s work shows how middle managers can become powerful “change intermediaries” when supported and intentionally positioned.

(From Blaming the Middle to Harnessing its Potential: Creating Change Intermediaries) - Rouleau describes the micro-practices of sensemaking and sensegiving—how managers interpret and “sell” change through everyday conversations and routines.

(Micro-Practices of Strategic Sensemaking and Sensegiving: How Middle Managers Interpret and Sell Change Every Day, Journal of Management Studies) - Huy’s research highlights an uncomfortable truth: successful change requires emotional work. Middle managers often do the emotional balancing—between continuity and radical change—because they are close enough to read the organization’s real temperature.

(Emotional Balancing of Organizational Continuity and Radical Change: The Contribution of Middle Managers, Administrative Science Quarterly)

So yes: line managers matter. But the dangerous leap is this:

“Because managers matter, we can outsource change to managers.”

That fails because managers typically lack:

- bandwidth (operations always wins)

- skill (sensemaking, resistance handling, coaching, reinforcement)

- authority (local power to remove barriers)

- a system (cadence, metrics, governance, escalation routes)

In other words: accountability without enablement.

3) Why the “project manager will do it” assumption creates predictable failure modes

Project managers are measured on scope, schedule, and budget. Even excellent PMs will default to what the system rewards: delivery certainty.

But the research on change recipients shows that reactions to change are shaped by factors like perceived fairness, trust, support, and personal impact, many of which sit outside a PM’s direct control.

(Change Recipients’ Reactions to Organizational Change: A 60-Year Review of Quantitative Studies, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science).

Also important: readiness is not the same as “not resisting.” Armenakis et al. framed readiness for change as beliefs/attitudes/intentions that precede support or resistance—and importantly, readiness can be influenced by deliberate actions from change agents and leaders. (SAGE Journals)

So the predictable failure mode is:

- the PM communicates and trains

- the org still isn’t ready

- local leaders are not equipped to reinforce

- people revert under pressure

This is not incompetence. It’s a structural mismatch of roles and incentives.

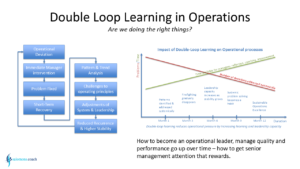

4) What high-performing change organizations do: they build an operating model, not a toolkit

Organizations that deploy change well don’t “add change management.” They institutionalize it, often quietly, through a clear operating model:

The core design principle

- Line owns adoption outcomes.

- Change capability enables adoption.

- Project/program owns solution delivery.

- Sponsor owns priority and reinforcement.

This lines up strongly with Prosci’s recurring findings that active and visible sponsorship is the top contributor to success, and that supporting people managers matters. (proscieurope.co.uk)

The practical mechanism: implementation climate

High performers intentionally shape “implementation climate,” i.e., the shared perception that using the change is expected, supported, and rewarded. (journals.aom.org)

In practice, that means:

- leaders make the change non-optional through choices and trade-offs

- managers are coached to run local sensemaking

- obstacles are removed fast (process, IT, policy, staffing)

- reinforcement is designed into the rhythm (KPIs + reviews + recognition)

5) The “missing layer” most organizations don’t name: change leadership behavior

A lot of change conversations focus on comms and plans. But leadership behavior is often the hidden variable.

Higgs & Rowland studied behaviors of successful change leaders and showed that how leaders lead change matters materially—not only what they communicate. (SAGE Journals)

And Herold et al. found that transformational leadership relates strongly to commitment to change—especially when personal impact is high. (PubMed)

Put bluntly:

When impact is high, “good comms” is not enough. People watch leaders for cues of safety, meaning, and seriousness.

6) Resistance: stop moralizing it, start diagnosing it

Many organizations talk about resistance as if it’s a defect in employees. The research is more nuanced.

Oreg developed and validated a scale showing that dispositional resistance varies by person (routine seeking, emotional reaction, cognitive rigidity, short-term focus). (PubMed)

But recipient reactions are also shaped by context: trust, justice, support, perceived need, and personal impact. (SAGE Journals)

Translation for leaders:

- Some resistance is personality-linked

- A large part is context-created (how the change is led and experienced)

So instead of “overcoming resistance,” treat it as signal:

- values-fit problem?

- fairness problem?

- capacity problem?

- competence problem?

- trust problem?

7) A simple diagnostic you can give your readers

If change is being “pushed” onto line managers or project managers, ask these five questions:

- Who owns adoption metrics? (not project milestones)

- What is the sponsor’s weekly behavior? (not their kickoff speech) (proscieurope.co.uk)

- What is the manager enablement plan? (skills + time + tools)

- How will implementation climate be shaped? (signals, rewards, barriers removed) (PMC)

- Where is the change capacity located? (CoE, embedded BPs, change leads)

If you can’t answer these, you don’t have a change approach—you have hope.

Closing: the strongest conclusion you can land

Organizational change management is not a “nice-to-have” function and not a comms layer. It’s the discipline of building adoption conditions: readiness, sensemaking, reinforcement, and an implementation climate that makes the new way stick.

So yes: line managers are essential. Project managers are essential. But neither can substitute for a change operating model.

Successful organizations don’t “assign change.” They engineer it.

References you can cite (credible backbone)

- Klein, K.J. & Sorra, J.S. (1996). The Challenge of Innovation Implementation. (journals.aom.org)

- Prosci (2018). Best practices in change management, Prosci Benchmark Report Executive Summary

- J. Balogun (2003). From Blaming the Middle to Harnessing its Potential: Creating Change Intermediaries). Britisch Journal of Management.

- Weiner, B.J. et al. (2011). The meaning and measurement of implementation climate. (PMC)

- Armenakis, A.A., Harris, S.G., & Mossholder, K.W. (1993). Creating Readiness for Organizational Change. (SAGE Journals)

- Oreg, S. (2003). Resistance to change: Developing an individual differences measure. (PubMed)

- Oreg, S., Vakola, M., & Armenakis, A. (2011). Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review. (SAGE Journals)

- Balogun, J. (2003). From blaming the middle to harnessing its potential: creating change intermediaries. (Lancaster University research directory)

- Rouleau, L. (2005). Micro-practices of strategic sensemaking and sensegiving. (Wiley Online Library)

- Huy, Q.N. (2002). Emotional balancing… the contribution of middle managers. (SAGE Journals)

- Higgs, M. & Rowland, D. (2011). What does it take to implement change successfully? (SAGE Journals)

- Herold, D.M. et al. (2008). Transformational/change leadership and commitment to change. (PubMed)

- Prosci benchmarking summaries on sponsorship and manager support (practitioner evidence, widely used). (proscieurope.co.uk)